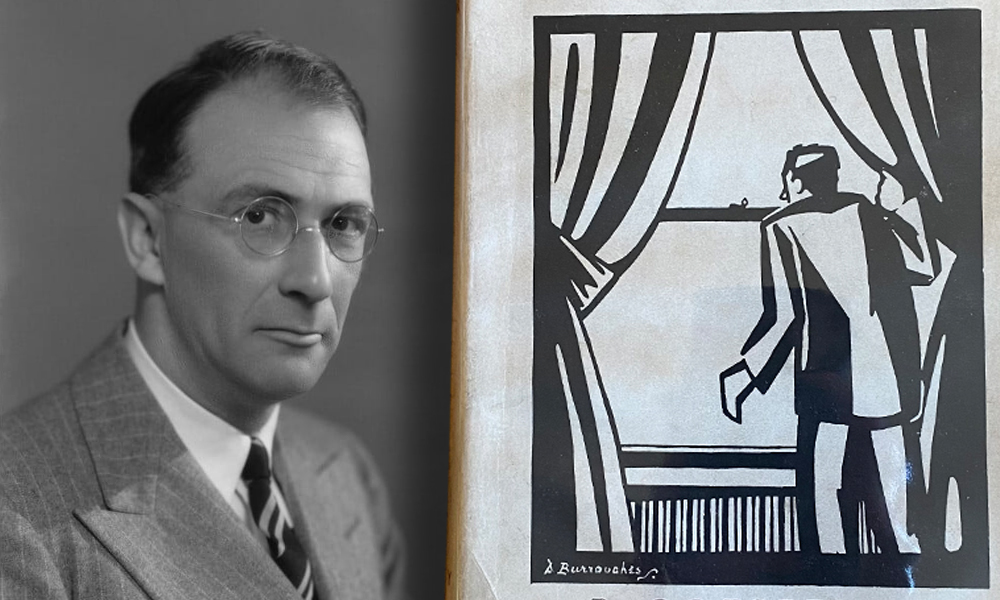

Payment Deferred, by C. S. Forester

Bill Ryan

Forester’s best-known work is, again, due to a film adaptation: boats evidently being a big thing with Forester, he published The African Queen in 1935, which was of course turned by director John Huston, co-screenwriter James Agee, and stars Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn, into the 1951 film of the same name, a film that still stands as one of the most famous and beloved from Hollywood’s Golden Age. So clearly, in his day Forester had cornered the market on aquatic adventures, and for a long time I assumed that’s all that C. S. Forester wrote. Recently, however, I stumbled across a copy of his 1926 novel Payment Deferred, a merciless, hardboiled crime novel, my favorite type.

There are essentially two types of crime novel, if you’ll permit me to simplify things horribly: in the first, the story is about detection. In other words, someone, either a professional or an amateur, is investigating a crime, and trying to bring the guilty party to justice. There are variations on this, and there’s a lot you can do within that framework, but for the sake of argument, that’s one type. The second is from the point of view of the criminal, and is either about guilt, or its absence. Payment Deferred is of the latter type.

The novel is about William Marble, who is in desperate straits when we first meet him. A bank employee with a wife who is careless with money, two children about to enter the next and more expensive rounds of schooling, mixed with his own financial mistakes and a whisky habit that is creeping into dangerous territory, we meet Marble on page one, stressing over his family budget. As this is a novel about a man who feels enough despair that he feels the need to go to horrible extremes to extract himself, it’s interesting that at no point does Forester feel it necessary to make Marble likable. In the first few pages, he is needlessly sharp and punitive towards his children, John and Winnie, who have done nothing worse than keep him from his drinking. He is also callous and rude towards his wife, Annie, a woman who, as the novel progresses, will come to learn many awful things about her husband, including the possibility that not only does he no longer love her, he may never have.

The plot kicks off very quickly, when James Medland, Marble’s nephew, suddenly appears at their door. Marble hasn’t seen Medland since Medland was a child, nor has he seen his sister, the man’s mother, since then. Medland is there to inform Marble that his sister has died. Barely registering, or caring about, this fact, Marble instead takes note of Medland’s fine clothes, and even gets a glimpse inside his wallet, which includes a lot of five pound notes, as well as hundreds of dollars and Treasury notes, obtained for Medland’s trip from Australia, where he goes to school. Very shortly, a scheme occurs to Marble, and having sent his family to bed long before, he fixes Medland a drink, to which he adds potassium cyanide, a supply of which he has with his photography equipment, photography being a hobby of his, a concoction which kills Marble’s nephew quite quickly. Marble takes the money and buries the young man in the back garden.

The plot then becomes complicated, somewhat needlessly so. The gist is that, in order to make it hard to track back to him, and using a confederate to invest the Treasury notes under the informed belief that the franc is about to rise in value, Marble and his family become rich. There is no more need to budget, no more need to go to work on time, or to be sober while there. The children’s education is paid for. What cannot be done, however, is the family cannot move, nor can they hire any servants, because almost as soon as the act was done, Marble became understandably obsessed and paranoid that someone will discover Medland’s body, buried in the garden.

Forester writes that Annie sees her husband staring out the window at the garden for hours. Annie’s dull-wittedness is so stressed by Forester that her ability to eventually connect the dots is a little bit hard to buy, but somebody had to connect those dots, because Forester is going somewhere with all this. The meaning behind the title Payment Deferred is easy enough to tease out – it’s essentially the same metaphor used by James M. Cain when he called his 1934 novel The Postman Always Rings Twice; and interestingly enough a major plot turn occurs at the end of Forester’s novel when a letter is delivered – but the glib tone of it indicates more about the novel than that it will feature karmic retribution.

For one thing, the novel is quietly morally grotesque, and not just in how quickly and easily its protagonist resorts to murder. He does not experience guilt, or if he does he has kind of sublimated that into a paranoid drive for self-preservation. This can be read as guilt: they can never know what I have done, because deep down I know that what I have done is bad. But it could also be: they can never know what I have done, because for some reason they think what I’ve done matters. Either one could be the case with Marble, but his indifference over his sister’s death suggests guilt is an unfamiliar emotion, and a later reaction to what should be a more emotionally shattering death reads on Marble as just another burden to be gotten through.

Because make no mistake, Payment Deferred about the utter destruction of a family, brought about by the selfish, amoral laziness of its patriarch. A man who the reader never encounters in a good mood (except once or twice when he’s indulging heedlessly in his money, though his mind is at all times too feverish with paranoia for this to be a regular occurrence) and who may have never been in one, something with which his family has had to put up with for years:

But to-day there was no smile. Marble’s set, dull look frightened her, it was so like the look had had worn in the bad time. A little shudder ran through her, as she realized that it was calling up within her the same sensations, as though they were echoes, that she had known during the same period. A light had gone out in the world.

At the same time, Payment Deferred is a blackly comic novel, though it takes a while for that to sink in, or it did with me, anyway. But due to his unwillingness to move houses, Marble has to find some way to flaunt his wealth, and so he decks out his modest little home with the most vulgar gold gilt furniture. All the neighbors are aware of both its general gaudiness and the sheer amount of it. And in addition to two further deaths that result, both directly and indirectly, from Marble’s willingness to commit murder, another way the family is destroyed is in how the daughter, Winnie, becomes spoiled through her father’s thoughtless expenditures from a seemingly bottomless store of wealth. So Marble can be blamed for three deaths, and for ruining his daughter’s personality.

If that seems as glib as the title, well, the full emotional and tonal thrust of the novel is driven home by the last paragraph, which I will not quote. Suffice it to say, the novel’s strange tone, Forester’s seeming emotional indifference, both toward his characters and instilled into them, takes on a new, sharper meaning. Given the inhumanity on display in the story being told, why should the teller’s voice betray any more compassion?

It’s like a plot twist, but instead it’s a twist in tone. The tone is explained, not the plot. There’s a little bit of anger from Forester, that people can behave like this, and do these things. A little bit of cold-blooded satisfaction in the revenge he is able to take vicariously.

Thanks for reading - but we’d love feedback! Let us know what you think of Bill’s thoughts at Bluesky.

Mythaxis is forever free to read, but if you'd like to support us you can do so here (but only if you really want to!)